Identifying violence

Systemic and structural violence refers to forms of violence that are integrated in and perpetuated by social, economic, political and cultural systems. They are often invisible and normalized, making their identification and resolution complex. This violence causes significant long-term harm to individuals. Various forms of violence can be intertwined (for example, violence and intersectional discrimination) and often form a continuous chain of interrelated violences, called a continuum of violence. This makes survivors or victims particularly vulnerable and isolated. The invisiblization of violence is reinforced by the prevalence of stereotypes that deny or minimize its existence, such as situations of domination and abuse, rape culture, exoticization, ableism, etc.

Most higher education institutions (circus schools, art schools, preparatory schools, etc.) and public and private organizations (festivals, performance venues, cultural and artistic centers) have set up awareness-raising and training initiatives as well as systems for reporting discrimination and violence, and support for victims. However, these systems have been put into place within institutional frameworks that often include their own constraints (i.e. because of legal obligations, or due to institutional performativity, etc.) leading to varying degrees of efficacy and support (administrative, therapeutic, disciplinary support). The ideal would be to address these issues individually and collectively, by questioning existing systems, questioning one’s own practices, and learning to identify violence. Sustaining these efforts increases survivors’ access to support and helps ensure attentive, high-quality, and efficient care.

Violences: what are we talking about?

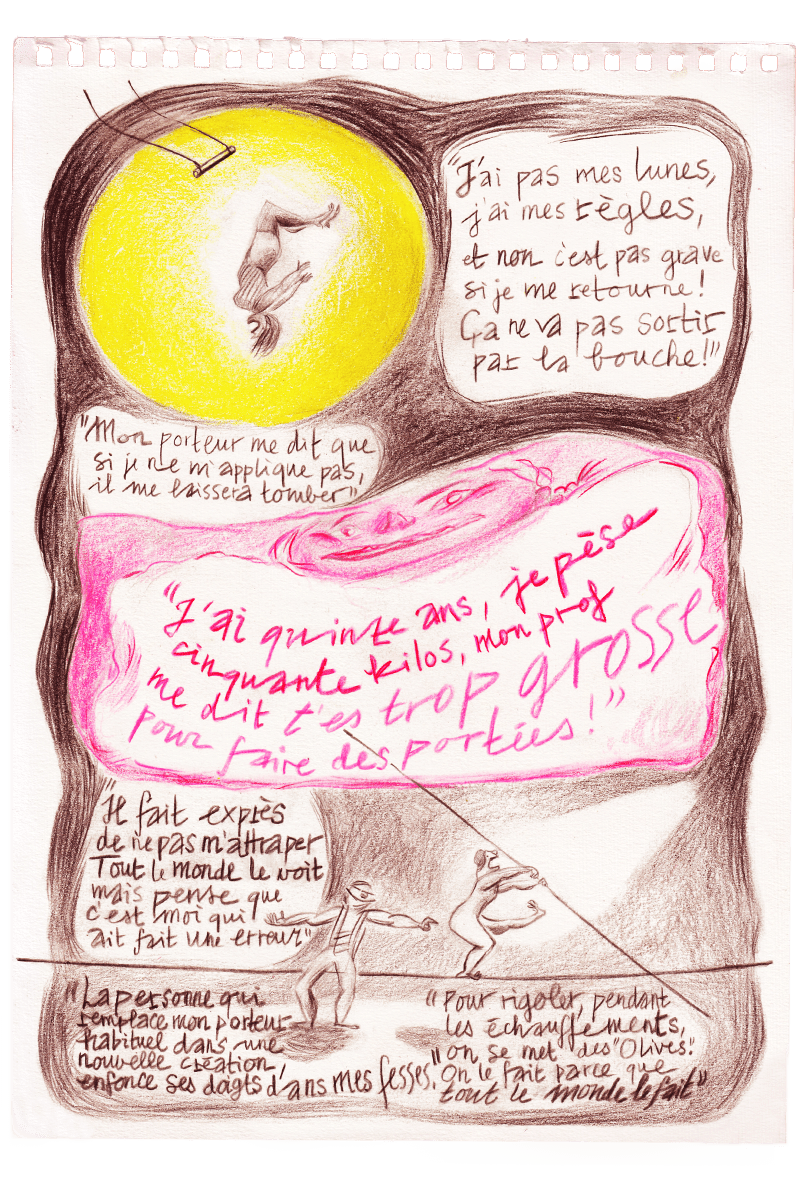

It’s important to refer to each country’s legal definitions of violence. This makes it possible to identify violence, define it, and understand what can be done within a specific spatial and temporal framework. Education, reading, and attending themed discussions all aid in an in-depth understanding of the mechanisms of violence. This knowledge also leads to an understanding of the terms that describe physical or psychological violations based on gender, sexuality, race, age, social and cultural origins, abilities, etc. Violence happens along a continuum and adopts a cumulative and combinatorial dimension (pyramid of discrimination and violence, intersectional discrimination and violence). This continuum can include forced physical contact, disrespectful attitudes, hurtful or abusive language, inappropriate gestures, physical and sexual assault, harassment, rape, physical violence, etc. Contexts that are conducive to violence, or that do not work to end violence, by nature produce situations of endangerment, isolation, self-destruction, and maintain self-blame among victims.

As violence is often hidden or otherwise minimized, the consequences faced by victims are often unknown or ignored. However, the psychological and physical effects of such violence are numerous and have a considerable negative impact, such as triggered traumatic memories and flashbacks. This affects all aspects of life, including the personal, professional, familial, and over a long period of time. The consequences of violence are multiple and cumulative (weight gain or loss, stress, anxiety, sleep loss, difficulty concentrating; depression, isolation, loss of trust in others; loss of awareness, poor performance, interruptions in education or careers). We often speak of an artistic “family,” which is a relatively small circle of people. This situation exacerbates the difficulty of healing from violence, as it is difficult to reconstruct a professional network or to start again elsewhere. Violence and its consequences can thus follow victims throughout their lives or careers.

Violent spaces and contexts

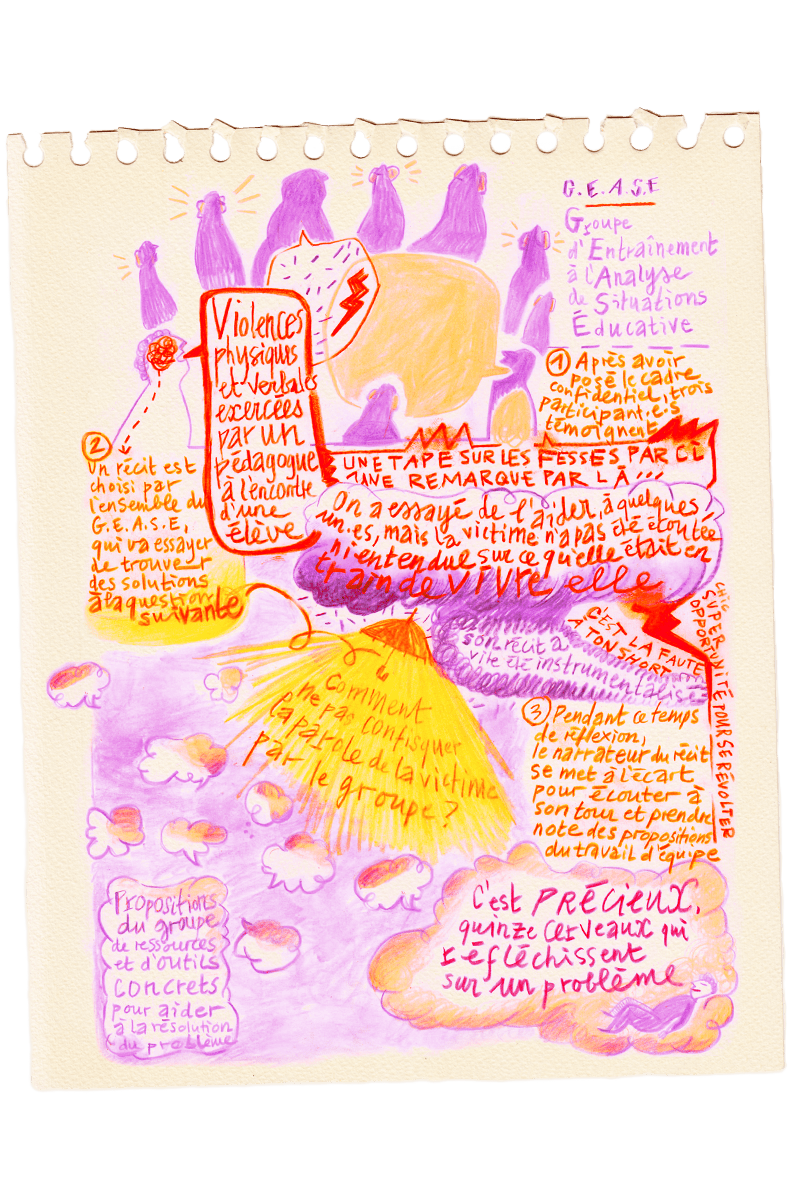

Artistic and circus and spaces are very small worlds. Throughout our careers we meet, collaborate with, and interact with the same small set of people, whether it be in training contexts or for work. “Everyone” knows each other. The boundaries between the formal and the informal are often difficult to identify. As colleagues, we speak to each other informally, we stay with each other, we go out for drinks, we tour together. In this context, men still largely occupy positions of power as directors, teachers, venue programmers, distributors, funders. The power dynamics facilitate power abuses. Aggressors, often well placed within artistic networks, can strategically make use of all these factors, and create the contexts for their impunity. Abusers teach, help network, do favors, and appear to be friendly people, generous with their time, “genuinely” caring about the victims. Sometimes aggressors even show activist or feminist commitment and become “figureheads” who explicitly present themselves as “rebels” or agitators; they refuse the rules of propriety and are admired for their strong personalities.

For the victims, speaking out against the aggressions of a colleague or a teacher can be particularly difficult, for many reasons: everyone will know; he is the only teacher in his specialty; he is part of diploma or hiring committees; we are part of the same troupe; we will systematically run into him at events and festivals; he is part of a grant-giving committee; he directs a venue, etc. Abusers also routinely seek to isolate their victims, instructing them not to tell anyone, threatening them, or spreading rumors about them. Long-term professional relationships (teacher-student, company director, or other work partnerships) often give rise to power dynamics that encourage control and domination. In these cases, the power asymmetry and physical risks are such that any denunciation is disproportionately costly to the victim. Faced with these factors and tactics, victims are often not listened to or believed. Often friends and colleagues know and appreciate the aggressor, or fear him, or cannot do without him, etc. The silence surrounding the issues of violence in artistic and educational networks makes it all the more difficult for victims to clearly identify situations of violence to which they are subjected. They tell themselves: I’ve surely misunderstood the situation; it’s just like that in our field; everyone does it; we all have to go through it; etc. Even when identifying problematic and violent situations, victims are often encouraged to keep quiet: it’s nothing, you’re exaggerating, I don’t believe he would do that, etc.

Listening and consent

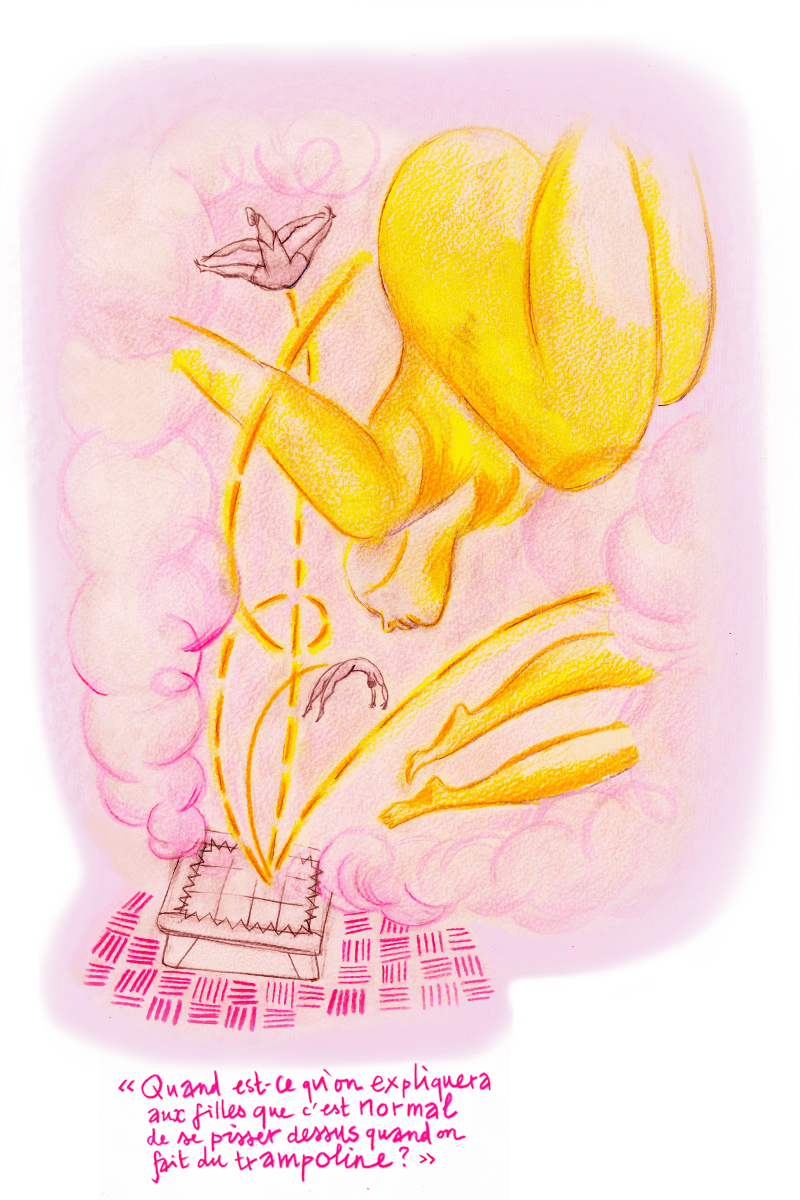

It’s common to dispense with the protocols aimed at ensuring the consent of students/learners, performers, and employees due to working, teaching, and training conditions that include large groups, limited time, and “habits.” Violent words (directions, “recommendations,” “jokes”) gestures (physical contact or proximity, sudden change of partner), and requests (to “go further,” to accept partial or full nudity, to take dangerous risks, etc.) are addressed and reiterated toward teams, students/learners, and performers, for the “sake of” efficiency, to uphold an artist’s vision, or within improvisations. However, it is of course essential to ensure everyone’s consent at each stage of the work and/or training process.

In many situations, lack of consent is expressed through physical or non-verbal signals such as withdrawal, unease, non-responsiveness, or avoidance. It’s essential to be attentive to these signs. Consent is only valid when it can be expressed clearly, freely (i.e. without being in a state of psychological and/or physical vulnerability, without constraints, without pressure, without threats, without surprises), specifically (for a given situation or task) and renewed at each stage of the training or creation process. Beyond the legal framework, consent is part of relationship ethics and depends on an empathetic approach. We must be able to listen, so as to create teaching and working relationships either without endangerment, or with an awareness of the potential risks taken.

Preventive measures and taking action

Violence emerges structurally within the context of artistic activities, in the same ways it emerges in contemporary society. An essential first step in preventing violence lies in ensuring that it’s safe to speak about violence within a given setting, i.e. at a school or training space as well as in a festival, an institution, a cultural or artistic venue. It’s necessary to break the silence and treat these topics as legitimate, deserving their own safe space during training, teaching, creation, and touring. This also creates capacity to collectively identify situations of violence and prevent them from happening, for oneself and for others.

Putting in place clear, accessible protocols is a next step. This protocol can include: a unit fighting against violence and discrimination, forms for reporting violence, workshops, awareness-raising and outreach, a charter of good practices and ethics, an internal code of conduct, a transmission chain for reports, etc. One key to establishing trust and creating space that is conducive to speaking out and reporting, as well as preventing possible situations of violence, is the creation of a network of people who participate in regular workshops, and who are visible and available (sometimes known as “equality advisors”). The more that members of a team (whether it be educational, artistic, or administrative) are collectively trained in these issues, the more care and support they have to offer to victims. Training is also crucial in preventing violence.

It’s important to validate the victims’ testimonies (“I believe you,” “what you are experiencing is serious”) without questioning their experiences; to listen to and respect what next steps they are considering, and to guide them to a set of resources, organizations, non-profits, and existing systems that have developed concrete expertise around these issues. It’s important to keep caution and care at the center of the process. One must respect one’s own limits and those of the victim, while thinking about one’s own safety and that of the person who testifies (i.e. consider the potential negative consequences, and avoid further endangering the victim). Lastly, victims must systematically be asked how they wish to proceed, and according to what temporality. It’s essential to act only with the victim’s consent (to not do things “in their place” or “for them”), and to verify consent at each stage of a process.

Resources

- MANNING, E. (2007), Politics of Touch: Sense, Movement, Sovereignty, University of Minesota Press

- Les mots de trop

- Journal La Crecelle

- Collectif Féministe Contre le Viol-CFCV

- Collectif de Lutte contre le Harcèlement sexuel dans l’enseignement supérieur

- Association Européenne contre les violences faites aux femmes au travail

- Espace Info

- Arts sainement

- Culture en Jeu

- Artandcare

- Defenseur des droits

- Documentaire « Briser le silence de amphis »

- Protection de l’enfance suisse (notamment thème violence sexuelle)

- Aide-aux-victimes

- ESPAS – Espace de soutien et de prévention abus sexuels

- Viol – Secours, Association féministe de lutte contre les violences sexistes et sexuelles

- Association VIA

- Association And You

- ProJuventute

- Tu t’en sors ?

- Contre les abus sexuels dans le sport (notamment brochures Lignes directrices contre les abus sexuels dans le sport, Proximité – Distance – Limites et Orientation pour les ressources juridiques)

- Capsules vidéo sur le harcèlement

- Podcast RTS La Première, Prévenir les violences sexuelles sur les enfants

- Podcast QuasiSamediProd, Le Petit Chat est mort, sexisme dans l’enseignement du théâtre

- Podcast ArteRadio Un podcast à soi. Sexisme ordinaire en milieu professionnel

- Podcast Emotions (au travail), Le bémol, sexisme dans la musique

- Podcast France Culture, LSD La série documentaire, Place aux gros

- Podcast BINGE, Kiffe ta race, nos corps appropriés

- Swiss Sport Integrity

- Clickandstop

- Helpline LGBTIQ

- PAV (Pôle Agression et Violence)

- Violences: que faire?

- Service de lutte contre le racisme (SLR)

- Pro Infirmis

- Epicène

- Fondation Agnodice

- ciao.ch

- ontecoute.ch

- ZEILINGER, I. (2018), Non c’est non. Petit manuel d’autodéfense à l’usage de toutes les femmes qui en ont marre de se faire emmerder sans rien dire, La Découverte.